If you know me at all you'll be aware that I never like to have one piece of sports equipment when 17 will do. The cupboard under the stairs is a veritable Aladdin's Cave of sporting tech with lost instruction manuals and flat batteries, and until recently that included a super-duper watch that promised it would count my laps in the swimming pool. It ended up in the cupboard under the stairs because it didn't do this very well at all.

It's not a manufacturer fault; it's quite reasonably designed for people who can swim and therefore turn properly, and apparently my once-a-length impression of some badly wrapped chicken breasts in a faulty blender doesn't count. So I reverted to technology from a simpler age.

You've probably seen a clock like the one above at your local swimming pool, but it's less likely that you've ever used it. It's called a Pace Clock, and it's an old-school, effective, and utterly brutal tool designed to turn the simple counting of seconds into a refined form of swiming torture.

Brockwell Lido, scene of many battles with The Clock

The concept is simple. The double-ended red/black hand counts seconds, sweeping continuously around the clock face. If you know where either the black or red hand was when you started, then by looking at it when you finish, you can easily calculate how long you took.

For example, I want to swim 100m, in a 50m pool, in 1 minute 45 seconds. I start in the shallow end with the red hand at '12'. When I return to the shallow end, it should be at the 'quarter-to' position. If I want to swim 1000m at that same 1:45 pace, I can check I'm keeping on that pace by ensuring that the position of the red hand moves back by 15 seconds, every time I return to the shallow end.

As you reach for the wall, you glance at the clock and pray you're keeping up. It never waits.

As the metres tick up, and keeping on-pace gets progressively harder, time simultaneously speeds up on the clock, but slows down for your shoulders, lungs, and general will to live. Perhaps swimmers, and athletes in general, know better than most that Einstein knew what he was talking about. Time really is relative.

Recently that SuperWatch had to come out of retirement (the GPS being a bit less fallible than the lap counter) as I've stopped doing my long swims in the pool and started doing them in the sea.

Before my training moved down to Dover for long swims, my longest pool swim was 12km, which took me just under 4 hours, so a pace of more or less 2 minutes per 100m.

Read it and weep

My hope was that as my training increased, that I would be able to up the distance, but maintain that 2 minutes / 100m pace. That was until I took the SuperWatch down to Dover, did a 5 hour swim, and downloaded the data. Having digested the results, I can now officially reveal that I have as much chance of doing this as Vladimir Putin does of being made a Patron of Amnesty International.

My best average pace for 5 hours in the sea is 2:20/100m; my worst (in heavy swell) is an execrable 2:41/100m. And that's just for 5 hours. As Donald Trump somewhat evasively says when asked what 2 plus 2 equals, "you do the math".

I have, and though it was a somewhat humbling experience, it's also been helpful. I'll admit I started this journey with lofty ambitions of posting a good time - maybe even opening a little can of whoopass on David Walliams - but now I'm thinking about it all differently.

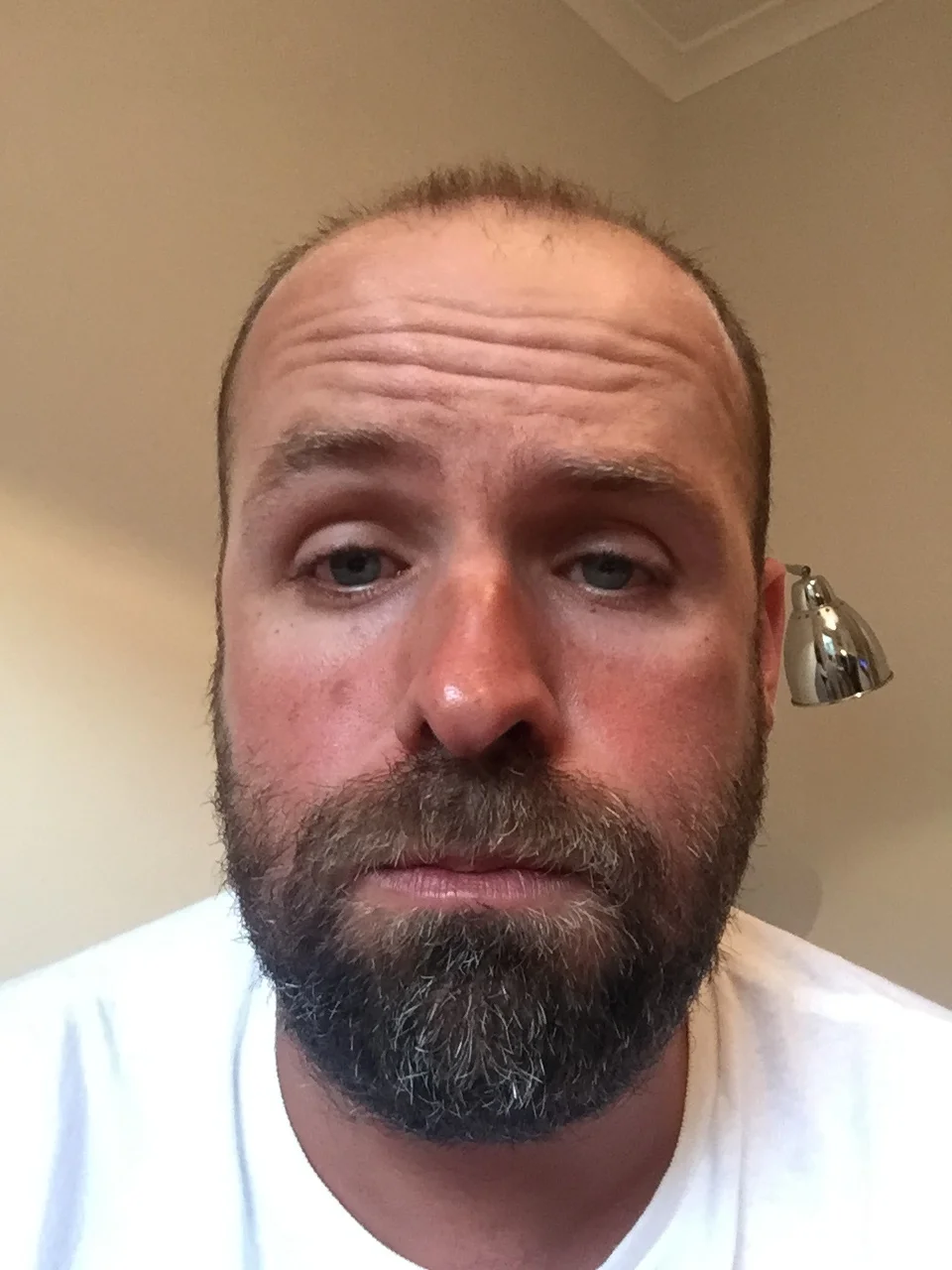

Tired with an excellent goggle tan after a 5-hour swim

Recently when I swam to the beach at Dover harbour to be fed, Nick Murch, a member of the beach team and a channel soloist himself, introduced me to another volunteer who was feeding on the beach, who he described as 'Channel Royalty'. Her name is Sue Daley, and last year Sue successfully swam the channel in 23 hours and 16 minutes.

In 2012, Australian Trent Grimsey set the current record in a scarcely believable 6 hours and 55 minutes. That's an average pace of 1:13 / 100m, and an extraordinary achievement.

Two incredible swims, two extraordinary people. I don't know the answer, but it's an interesting question as to which of these swims required greater determination, desire, and fortitude. Their times alone don't seem sufficient to answer it, and maybe that in itself is an answer of sorts.

Anyway, this is all by way of saying that like most aspiring soloists I won't be wearing a watch on my channel attempt, because it won't tell me anything useful. So much can change during the course of the journey, the fact that you've swum to point A in a certain time doesn't mean all that much. What you've given already is much less important than what you have left.